As the current COVID-19 outbreak so painfully demonstrates, ventilators are a critical piece of medical equipment for addressing pandemic-scale morbidity for viruses that affect the human respiratory system. The recent New York Times (NYT) article The U.S. Tried to Build a New Fleet of Ventilators. The Mission Failed. describes the U.S. government’s early attempts to address an acknowledged shortage of ventilators. The article reveals the full impact of the ventilator shortage the U.S. is experiencing now. When coupled with other factors, such as currently unstaffed federal healthcare agency leadership positions and reduced funding for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the COVID-19 pandemic will likely take a heavier toll on lives, society, and the economy than most Americans could ever have imagined.

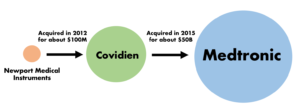

This commentary argues that there is more to the story behind the ventilator shortage. It asks a critical question: Has antitrust enforcement been sufficiently vigorous to preserve competition in the medical supplies and equipment markets? If the answer is “no,” it is clear that the benefits of competition through lower prices and higher levels of quality, innovation, and choice might have significantly reduced much of the loss of human life that we see now. A small manufacturer of ventilators, Newport Medical Instruments, is at the center of this story. So is Covidien, the larger firm that acquired Newport Medical. And so is Medtronic, the even larger firm that acquired Covidien only a few years later.

In the late 2000s, Newport Medical won a government contract to develop a relatively inexpensive ventilator that could be mass produced and deployed. As it readied prototypes to show the government, Newport Medical became a target for Covidien, which acquired it in 2012. The NYT article reports that some government officials and rival ventilator companies suspected that Covidien bought Newport to eliminate competition. Covidien already manufactured a line of ventilators, so by acquiring Newport Medical, Covidien could in theory strategically remove a rival ventilator manufacturer that might have grown to challenge it. Even as the Newport Medical ventilator story was unfolding, Covidien was acquired in 2015 by medical supplies and equipment manufacturer Medtronic. As one of a small number of large firms, industry sources list Medtronic as a top 3 competitor in equipment markets for cardiac, vascular, gastrointestinal, neurological, ear nose and throat, urology, diabetes, and patient monitoring applications.

The troubling story behind the abandoned Newport Medical ventilator program puts federal antitrust enforcement at center stage. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) reviews most mergers and acquisitions in the branded and generic pharmaceutical, pharmacy benefit management, medical distribution, and medical supplies and equipment markets. Merger control is designed to prevent acquisitions that are likely to substantially lessen competition, including acquisitions of head-to-head rivals; customers or suppliers; and potential rivals. Antitrust law is designed to prevent the adverse outcomes of anticompetitive mergers by stopping them in their “incipiency.”

Data sources reveal that between 2008 and 2014, Covidien made 17 acquisitions, or about 2.5 acquisitions per year. In 2012, the same year it acquired Newport Medical, Covidien made five other small acquisitions that most likely fell below the thresholds under the Hart Scott Rodino (HSR) Act, which governs which transactions are reportable to the U.S. government. Of Covidien’s remaining 12 acquisitions, many worth hundreds of millions of dollars each, we only know the antitrust fate of two–-Newport Medical Instruments and superDimension Ltd. These deals received “early termination,” or a green light to proceed after a brief initial antitrust review by the FTC. Covidien’s other acquisitions may have been small enough to be unreportable, or received a government request for additional information and ultimately let go. The FTC did not challenge any of Covidien’s acquisitions as violations of U.S. merger law. When it was acquired by Medtronic, Covidien had just come off a successful seven-year acquisition spree, making it a major addition to the company’s portfolio.

Over the last two decades, Medtronic made almost 70 acquisitions, or about three acquisitions per year. Picking up Covidien in 2015 marked the high point in the company’s spate of acquisitions when it added 10 firms to its portfolio. The FTC granted early termination to several acquisitions, including three very large transactions involving spinal surgery equipment and insulin pumps valued at between $1.7 and $3.9 billion. A substantial share of Medtronic’s total transactions in the last 20 years were either not reportable to the government, or were ultimately let go by the FTC. Only two acquisitions were challenged by the government, including Medtronic’s acquisitions of Covidien and Physio-Control. In the Covidien matter, the FTC required the divesture of a single asset to remedy competitive concerns—a drug-coated balloon catheter business.

This brief sketch of merger enforcement involving Newport, Covidien, and Medtronic demonstrates why strong antitrust enforcement is vital for promoting the competition that drives innovation, lower prices, and choice, but also for promoting redundancy in our critical supply chains. When a supply chain is under siege by an event like COVID-19 or other supply disruptions, the numbers and diversity of suppliers affect not only prices, but also human safety and public health. More competition, not less, assures a more adequate and diverse supply of equipment and better government preparedness for a catastrophic pandemic like the one we are currently experiencing.

We don’t know if Covidien’s acquisition of Newport Medical should have been stopped by the FTC on the grounds that it snuffed out a rival ventilator manufacturer. What we do know, however, is that current antitrust standards for acquisitions of smaller rivals are inadequate to address the burgeoning trend toward acquisitions of smaller rivals in sectors such as healthcare, digital technology, content, and others. Stronger antitrust standards are needed. Moreover, some of Covidien’s and Medtronic’s acquisitions of companies undoubtedly fell under the HSR reporting requirements thresholds. Acquisitions of smaller rivals that avoid antitrust scrutiny is an effective expansion strategy for creating very large firms. Lower HSR filing thresholds are essential for closing off this avenue.

Finally, the “wingspans” of companies like Medtronic—which has built out an ecosystem of interconnected markets of medical supplies and equipment—are vast. Without more information, it is difficult to understand how Medtronic’s $50 billion acquisition of Covidien rang only one small antitrust alarm bell in the single market for drug-coated balloon catheters. Enforcers have long focused their lens on narrow markets, often missing the “forest for the trees,” such as how acquisitions in large market ecosystems can help dominant firms leverage their market power from one market to another. In medical supplies and equipment, this leveraging can affect competition in any number of markets in related areas such as pulmonology, cardiology, and the vascular systems. Antitrust law should be updated to more accurately define and evaluate markets in such ecosystems.

In recent years, the media and Congress have focused on the foregoing types of competition issues, but almost exclusively in the digital technology sector. As this commentary demonstrates, these competition issues are obvious in sectors such as medical equipment and supplies, where the link between competition and public health is revealed by the COVID-19 crisis. They are also apparent in agricultural biotechnology, where the risk of exogenous shocks imperils a food supply chain that is dominated by only a few large players. The U.S. is witnessing the damage from four decades of under-enforcement of the antitrust laws, which leading progressive advocates have lamented for many years. U.S. antitrust enforcers should be tasked with determining how the ventilator crisis in the U.S. today might have roots in this saga.